39. Changing the script

Nothing about the scene had seemed more authentic or real, but everyone present would turn to everyone else and nod sagely. It was all a big racket.

The acting exercise that Mamet had invented and that Macy, in the summer of 1990, was trying to wean people away from calling “The Dirty Joke Game”—“It’s an exercise,” he kept insisting with an edge of impatience. “Let’s call it an exercise.”—turned out not to be at all what it sounded like.

It wasn’t about dirty jokes. It wasn’t about transgressive humor. It wasn’t about jokes at all except insofar as it used the narrative impulse—the universal human need to get to a punchline—to demonstrate something about the nature of dramatic tension.

Actually, that was only my perception and something I wound up arguing with Macy about much later.

The real purpose of the exercise was twofold: to get acting students to focus on one another rather than on themselves and to introduce them to the concept of “being in the moment,” which is what actors sometimes call it when scene partners are “working off” each other—when, in other words, what’s actually happening between them moment to moment determines how they say what they say.

Like much of what Mamet and Macy taught their students, the Dirty Joke Game derived from a famous teaching tool called The Repetition Exercise, invented by Sanford Meisner, in which two students bat a statement one has made about the other back and forth, over and over, until something that happens between them—some piece of behavior—creates a reason to “change the script.”

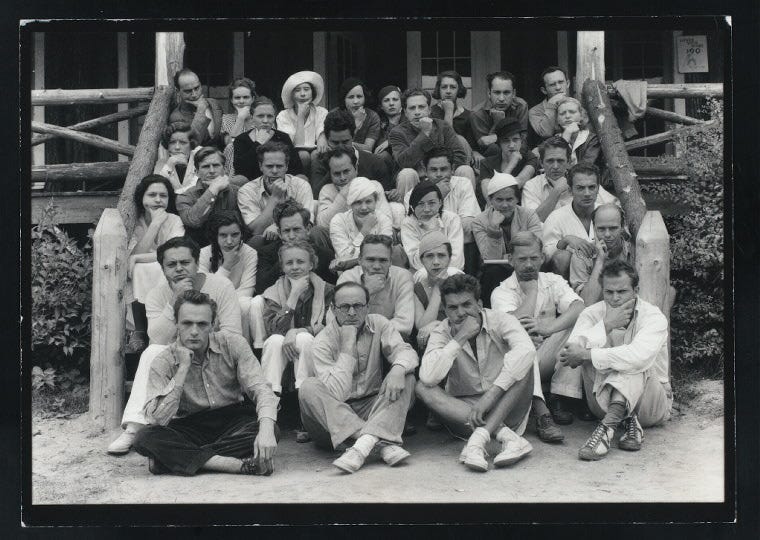

Meisner, like Lee Strasberg, had been a member of The Group Theater, but he was also a musician. Before becoming an actor (which he was very briefly) and an acting teacher (which he was for a long, long time) Meisner had studied to be a concert pianist, and integral to his ideas about acting was an understanding that in theater—as in any of the performing arts—two elements had to be reconciled: a fixed element, represented by the script or the score or the choreography, and an improvisational element that could not be fixed because it had to do with performance.

Two singers performing a duet could not hope to create anything of beauty without listening to one another: harmony and counterpoint are not created by notes projected into the aether in isolation but by voices leaning against each other, entwined like dancers or lovers.

Just so, if actors wanted a scene to resemble reality, they had to listen and respond to one another, interacting the way we all do in real life where how we say what we say is determined by the way someone else has said whatever came just before.

I only ever saw The Dirty Joke Game played once, in the summer of 1990, when Mamet taught it to the new crop of students on the first day of class. But it seemed to me the exercise had another purpose as well.

Whatever else it achieved, given the way Mamet presided over the exercise it served to establish the existence of perceivable truth.

Mamet called a couple of students to the front of the room and, having established that each knew a dirty joke, he instructed them to tell their jokes to one another, the object being to get to the end of your joke. The students weren’t allowed to talk at the same time, but neither would they be taking turns, exactly. Rather, what gave a student license to speak—to jump in with their own joke, picking up where they’d left off—was some weakness they had detected in their scene partner’s narration, some sort of glitch or period: a sigh, a breath, a balk or falter, a moment when the joke-teller paused for effect or perhaps ran out of steam.

Several rounds of the game were played that day with different pairs of students, and each time the same thing happened. Nobody got to the end of their joke. Nobody ever got very far at all because Mamet kept interrupting.

“Okay, stop! This is good,” he would say. Then he would draw attention to something that had just happened between the scene partners, how one had just plowed right over the other without paying attention, or how a student had missed some opportunity or made an observation and capitalized on it.

Mamet never simply stated what had happened, though. Rather he would turn to the class and exclaim: “Did you all see that? Did everyone see what just happened there, how he paused to take a breath, and she picked up on it and jumped right in? Did everyone see that?”

No one ever responded. All the same, the questions didn’t feel rhetorical. What Mamet seemed to be saying was that we weren’t in a space in which some authority figure would be riding roughshod over reality, making pronouncements about what everyone had seen. We weren’t going to have to pretend to think something had happened that hadn’t happened or to have seen something that wasn’t there.

To appreciate what a departure this was, you have to understand the kind of stranglehold that Method Acting still had on the culture, despite Strasberg’s death at the start of the decade, and the way matters of perception were handled within its domain.

Back then, serious acting was pretty much synonymous with The Actors Studio. There wasn’t really any reason for this. Strasberg had died in 1982, and Meisner and Stella Adler, another Group Theater alum, each ran schools that had produced plenty of famous, successful actors and were considered influential and important by those in the theater and film communities. There was also The HB Studio, run by Uta Hagen and Herbert Berghof. All basically taught some version of what members of the Group Theater had derived from Stanislavsky’s “System.”

Nevertheless, to a press and public that regarded themselves as sophisticated, acting could only be taken seriously as an art form if it came affixed to notions and practices that the Actors Studio brand had made famous, like the concept of “affective memory” and the idea that submerging oneself in past trauma was the path to great acting.

At one point in Isaac Butler’s beautifully written and meticulously researched 2022 history of Method Acting (The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act), he quotes a snippet from a 1960 article in The New York Times:

Although we have no formal national theater as such, in a way The Actors Studio has become that, for it has been demonstrating since its inception that there is indeed an American style of acting.

The context is Strasberg’s continued influence on the way people thought about acting. Despite its detractors, Butler writes, “little could dislodge the Method from its place of prominence. It was, as Strasberg’s devotees never tired of reminding people, a uniquely American acting style, and thus a mark of America’s artistic seriousness…”

Arguably by the 1970s, though, Method Acting had become a belief system whose only real tenet was a blind faith in itself, its primary purpose self-aggrandizement. And one place it exerted and consolidated power was the classroom, where uninspired and indifferent teachers coerced statements about what looks phony and what looks real from desperate and vulnerable students.

At the small liberal arts college that I wound up attending, the theater department was run by a serious Method Acting devotee. Both times I visited the campus before deciding to go there (for reasons I still can’t fathom), I sat in on an acting class and watched as the same thing kept happening. The professor would elicit an admission from a student who was working on a scene that some piece of acting hadn’t been truly felt and instruct the student to engage in some “affective memory” juju. When the scene was presented again, the professor would ask if that hadn’t felt better, more natural and real, and the student would agree that it had.

Anyone could see it was pure flim-flam: nothing about the scene had seemed more authentic or real, but everyone present would turn to everyone else and nod sagely. It was all a big racket.

Over the past decade, we’ve all of us become accustomed to the spectacle of large groups of people pretending to believe something manifestly untrue just because someone has said it. But during the second half of the last century, I think you would have had to go far and look hard to find people willing to say they had seen something they hadn’t seen because someone in a position of power said it had happened.

Outside of an acting class, that is.

At the school of acting run by The Atlantic Theater Company, Mamet wasn’t the only person who seemed to value empirical truth.

There are on YouTube plenty of videos in which someone teaches The Repetition Exercise, and I’ve probably hit most of them at one time or another. But I’ve never seen anyone introduce the exercise the way Macy did on the second day of class that summer.

He asked one student to make a statement about another student.

“He’s wearing a blue shirt,” the student said.

“He’s wearing a blue shirt,” Macy echoed, like he was thinking about it.

Then he turned to the class. “Is that true?” he asked.

Everybody said, “Yes.”

Macy asked if anyone disputed the statement, and everybody said, “No.”

“If we brought in more people, would any of them dispute it?” Macy asked, and everybody said, “No.”

“Then it’s true,” Macy said.